“Louis Braille: Dancing in the Dark” by Mrittika Sen, Santosh G Honavar. Vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 5–6 from: Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. Published on behalf of the All Indian Ophthalmological Society (Delhi, DL, IN) by Wolters Kluwer (Alphen aan den Rijn, ZH, NL) in 2022 Jan. URL: https://journals.lww.com/ijo/Fulltext/2022/01000/Louis_Braille__Dancing_in_the_Dark.3.aspx; DOI: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3048_21; PMID: 34937200; PMCID: PMC8917520.

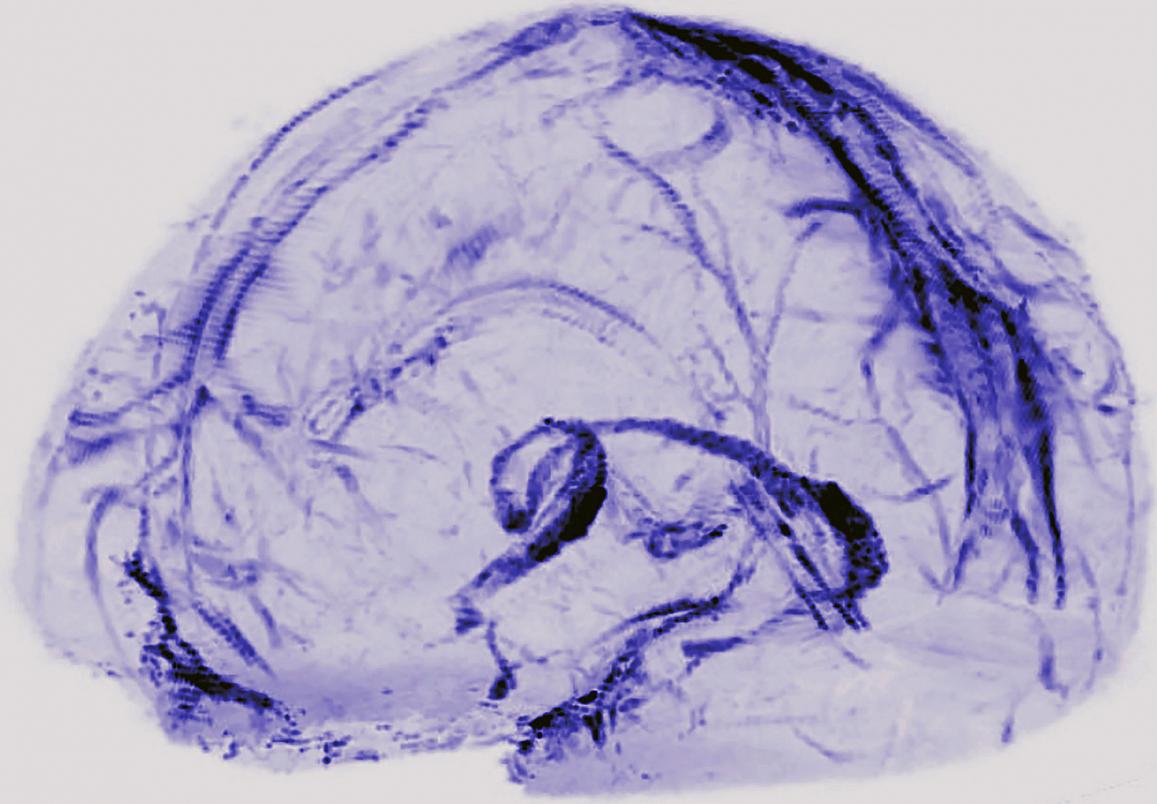

“Generation of Neurons in the Adult Brain.” Ch. 25 from: Neuroscience (2nd ed.) by Dale Purves, George J Augustine, David Fitzpatrick, Lawrence C Katz, Anthony‐Samuel LaMantia, et al. Published by Sinauer Associates (Sunderland, MA, US) in 2001. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10920/; ISBN: 0-87893-742-0.

“History of Blood–Brain Barrier.” from: The Arizona Brain Barriers Laboratory. Published by the University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ, US); copyright 2021; accessed 2024 Jul 19. URL: https://davislab.med.arizona.edu/history-blood-brain-barrier.

“Damage to a Protective Shield around the Brain May Lead to Alzheimer’s and Other Diseases” by Daniela Kaufer, Alon Friedman. Vol. 325, no. 5 from: Scientific American. Published by Springer Nature (London, ENG, UK) on 2021 May 01. URL: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/damage-to-a-protective-shield-around-the-brain-may-lead-to-alzheimers-and-other-diseases/; DOI: 10.1038/scientificamerican0521-42.

“Blood–Brain Barrier Breakdown: An Emerging Biomarker of Cognitive Impairment in Normal Aging and Dementia” by Basharat Hussain, Cheng Fang, Junlei Chang. Vol. 15, art. 688090 from: Frontiers in Neuroscience. Published by Frontiers Media (Lausanne, VD, CH) on 2021 Aug 18. URL: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2021.688090/full; DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2021.688090; PMID: 34489623; PMCID: PMC8418300.

“APOE4 Leads to Blood–Brain Barrier Dysfunction Predicting Cognitive Decline” by Axel Montagne, Daniel A Nation, Abhay P Sagare, Giuseppe Barisano, Melanie D Sweeney, et al. Vol 581, pp. 71–76 from: Nature. Published by Springer Nature (London, ENG, UK) on 2020 Apr 29. URL: https:////pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7250000/; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2247-3; PMID: 32376954; PMCID: PMC7250000.

“Interaction of the Rabies Virus P Protein with the LC8 Dynein Light Chain” by Hélène Raux, Anne Flamand, Danielle Blondel. Vol. 74, no. 21 from: Journal of Virology. Published by the American Society for Microbiology (Washington, DC, US) on 2000 Nov 01. URL: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jvi.74.21.10212-10216.2000; DOI: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.10212-10216.2000; PMID: 11024151; PMCID: PMC102061.

“Portals of Viral Entry into the Central Nervous System” by Phillip A Swanson II, Dorian B McGavern. Vol. 2, ch. 2 from: The Blood–Brain Barrier in Health and Disease, edited by Katerina Dorovini‐Zis. Published by the CRC Press (Boca Raton, FL, US) on 2015 Oct 06. URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282851330_Portals_of_Viral_Entry_into_the_Central_Nervous_System; DOI: 10.1201/b19299; ISBN: 978-0-42-907579-7.

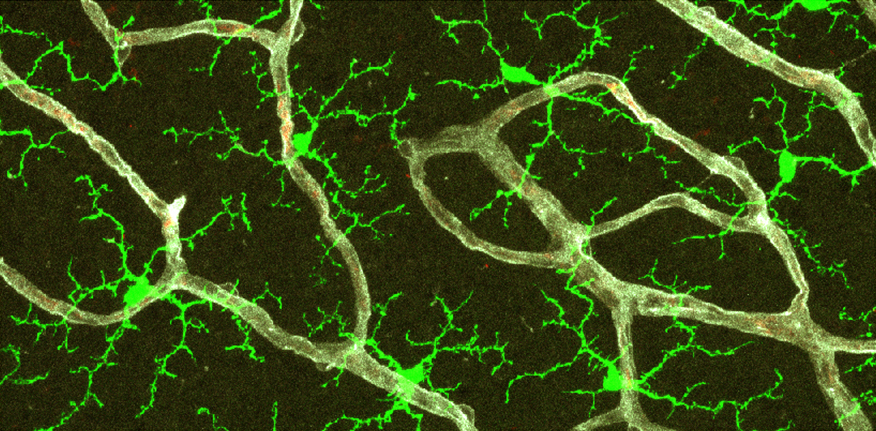

“Origin and Emergence of Microglia in the CNS — An Interesting (Hi)story of an Eccentric Cell” by Iasonas Dermitzakis, Maria Eleni Manthou, Soultana Meditskou, Marie‐Ève Tremblay, Steven Petratos, et al. Vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 2609–2628 from: Current Issues in Molecular Biology. Published by MDPI (Basel, BS, CH) on 2023 Mar 22. URL: https://www.mdpi.com/1467-3045/45/3/171; DOI: 10.3390/cimb45030171; PMID: 36975541; PMCID: PMC10047736.

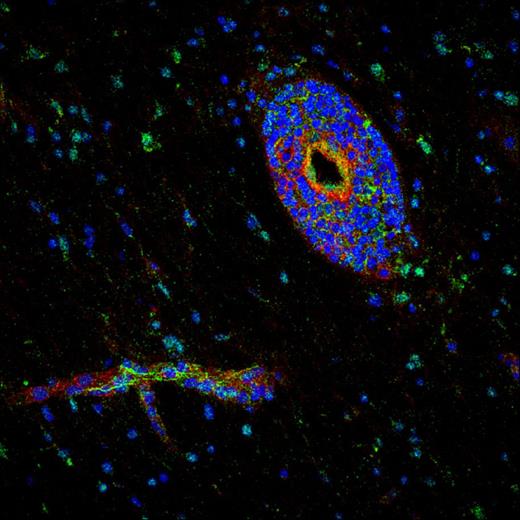

“The TSPO–NOX1 Axis Controls Phagocyte‐Triggered Pathological Angiogenesis in the Eye” by Anne Wolf, Marc Herb, Michael Schramm, Thomas Langmann. Vol. 11, art. 2709 from: Nature Communications. Published by Springer Nature (London, ENG, UK) on 2020 Jun 01. URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-16400-8; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-16400-8; PMID: 32483169; PMCID: PMC7264151.

“Microglia Activated by IL‐4 or IFN‐γ Differentially Induce Neurogenesis and Oligodendrogenesis from Adult Stem/Progenitor Cells” by Oleg Butovsky, Yaniv Ziv, Adi Schwartz, Gennady Landa, Adolfo E Talpalar, et al. Vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 149–160 from: Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. Published by Elsevier (Amsterdam, NH, NL) in 2006 Jan. URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1044743105002484; DOI: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.006; PMID: 16297637.

“Immune Cell Trafficking across the Blood–Brain Barrier in the Absence and Presence of Neuroinflammation” by Luca Marchetti, Britta Engelhardt. Vol. 2, no. 1, pp. H1–H18 from: Vascular Biology. Published by Bioscientifica (Bristol, ENG, UK) on 2020 Apr 10. URL: https://vb.bioscientifica.com/configurable/content/journals$002fvb$002f2$002f1$002fVB-19-0033.xml; DOI: 10.1530/VB-19-0033; PMID: 32923970; PMCID: PMC7439848.

“The Glymphatic System” by Lauren M Hablitz, Maiken Nedergaard. Vol. 31, no. 20, pp. R1371–R1375 from: Current Biology. Published by Cell Press (Cambridge, MA, US) on 2021 Oct 25. URL: https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(21)01130-1; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.026; PMID: 34699796.

“Activated Leukocyte Cell Adhesion Molecule Regulates B Lymphocyte Migration across Central Nervous System Barriers” by Laure Michel, Camille Grasmuck, Marc Charabati, Marc‐André Lécuyer, Stephanie Zandee, et al. Vol. 11, no. 518 from: Science Translational Medicine. Published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (Washington, DC, US) on 2019 Nov 13. URL: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw0475; DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw0475; PMID: 31723036.

“Cytokine Storm” by David C Fajgenbaum, Carl H June. Vol 383, no. 23 from: The New England Journal of Medicine. Published by the Massachusetts Medical Society (Waltham, MA, US) on 2020 Dec 02. URL: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra2026131; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra2026131; PMID: 33264547; PMCID: PMC7727315.

“How Cancers Escape Immune Destruction and Mechanisms of Action for the New Significantly Active Immune Therapies: Helping Nonimmunologists Decipher Recent Advances” by Jonathan L Messerschmidt, George C Prendergast, Gerald L Messerschmidt. Vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 233–243 from: The Oncologist. Published by the Oxford University Press (Oxford, ENG, UK) on 2016 Feb 01. URL: https://academic.oup.com/oncolo/article/21/2/233/6401118; DOI: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0282; PMID: 26834161; PMCID: PMC4746082.

“Chemotherapy and Immunosuppressant Therapy–Induced Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome” by Gurleen Kaur, Ibtisam Ashraf, Mercedes Maria Peck, Ruchira Maram, Alaa Mohamed. Vol. 12, no. 10, art. e11163 from: Cureus. Published on behalf of the California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology (Fairfield, CA, US) by Springer Nature (London, ENG, UK) on 2020 Oct 25. URL: https://www.cureus.com/articles/40643-chemotherapy-and-immunosuppressant-therapy-induced-posterior-reversible-encephalopathy-syndrome; DOI: 10.7759/cureus.11163; PMID: 33251070; PMCID: PMC7688184.

“M1/M2 Polarization in Major Depressive Disorder: Disentangling State from Trait Effects in an Individualized Cell‐Culture–Based Approach” by Nicoleta Carmen Cosma, Berk Üsekes, Lisa Rebecca Otto, Susanna Gerike, Isabella Heuser, et al. Vol 94, pp. 185–195 from: Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. Published by Elsevier (Amsterdam, NH, NL) in 2021 May. URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889159121000519; DOI: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.02.009; PMID: 33607231.

“Targeting Neuro–Immune Communication in Neurodegeneration: Challenges and Opportunities” by Aleksandra Deczkowska, Michal Schwartz. Vol. 215, no. 11, pp. 2702–2704 from: Journal of Experimental Medicine. Published by the Rockefeller University Press (New York, NY, US) on 2018 Oct 09. URL: https://rupress.org/jem/article/215/11/2702/120279/Targeting-neuro-immune-communication-in; DOI: 10.1084/jem.20181737; PMID: 30301785; PMCID: PMC6219738.

“Taming Microglia: The Promise of Engineered Microglia in Treating Neurological Diseases” by Echo Yongqi Luo, Rio Ryohichi Sugimura. Vol. 21, art. 19 from: Journal of Neuroinflammation. Published by BioMed Central (London, ENG, UK) on 2024 Jan 11. URL: https://jneuroinflammation.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12974-024-03015-9; DOI: 10.1186/s12974-024-03015-9; PMID: 38212785; PMCID: PMC10785527.

“Photoresponsive Vaccine‐Like CAR‐M System with High-‐Efficiency Central Immune Regulation for Inflammation-Related Depression” by Yu Liu, Ping Hu, Zhiheng Zheng, Da Zhong, Weichang Xie, et al. Vol. 34, no. 11 from: Advanced Materials. Published by Wiley‐VCH (Weinheim, BW, DE) on 2021 Dec 12. URL: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/adma.202108525; DOI: 10.1002/adma.202108525; PMID: 34897839.

“Harnessing Regulatory T Cell Neuroprotective Activities for Treatment of Neurodegenerative Disorders” by Jatin Machhi, Bhavesh D. Kevadiya, Ijaz Khan Muhammad, Jonathan Herskovitz, Katherine E Olson, et al. Vol. 15, art. 32 from: Molecular Neurodegeneration. URL: https://molecularneurodegeneration.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13024-020-00375-7; DOI: 10.1186/s13024-020-00375-7; PMID: 32503641; PMCID: PMC7275301.

“Intrathecal Bivalent CAR T Cells Targeting EGFR and IL13Rα2 in Recurrent Glioblastoma: Phase 1 Trial Interim Results” by Stephen J Bagley, Meghan Logun, Joseph A Fraietta, Xin Wang, Arati S Desai, et al. Vol. 30, pp. 1320–1329 from: Nature Medicine. Published by Springer Nature (London, ENG, UK) on 2024 Mar 13. URL: https://www.cceb.upenn.edu/ifi/assets/user-content/documents/s41591-024-02893-z.pdf; DOI: 10.1038/s41591-024-02893-z; PMID: 38480922.

“Intraventricular CARv3-TEAM-E T Cells in Recurrent Glioblastoma” by Bryan D Choi, Elizabeth R Gerstner, Matthew J Frigault, Mark B Leick, Christopher W Mount, et al. Vol. 390, no. 14 from: The New England Journal of Medicine. Published by the Massachusetts Medical Society (Waltham, MA, US) on 2024 Mar 13. URL: https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2314390; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2314390; PMID: 38477966; PMCID: PMC11162836.

“The Rapid Isolation of Clonable Antigen‐Specific T Lymphocyte Lines Capable of Mediating Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis” by Avraham Ben‐Nun, Hartmut Wekerle, Irun R Cohen. Vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 195–199 from: The European Journal of Immunology. Published on behalf of the European Federation of Immunological Societies (EU) by Wiley‐VCH (Weinheim, BW, DE) in 1981 Nov. URL: https://journals.aai.org/jimmunol/article-pdf/198/9/3384/1432026/1700351.pdf; DOI: 10.1002/eji.1830110307; PMID: 6165588.

“Santiago Ramón y Cajal: Biographical.” Published by Nobel Prize Outreach (Stockholm, AB, SE); accessed 2024 Jul 20. Originally published by Elsevier (Amsterdam, NH, NL) in 1967. URL: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1906/cajal/biographical/.

“Golgi and Cajal: The Neuron Doctrine and the 100th Anniversary of the 1906 Nobel Prize” by Mitch Glickstein. Vol. 15, no. 5, pp. R147–R151 from: Current Biology. Published by Cell Press (Cambridge, MA, US) on 2006 Mar 07. URL: https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(06)01203-6; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.053; PMID: 16527727.

“Luis Simarro Lacabra” by Helio Carpintero Capell. From: El diccionario biográfico español edited by Carmen Iglesias. Published by the Royal Academy of History (Madrid, MD, ES); copyright 2018; accessed 2024 Jul 20. URL: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/14994/luis-simarro-lacabra.

“The Father of Modern Neuroscience Discovered the Basic Unit of the Nervous System” by Benjamin Ehrlich. Vol. 326, no. 4 from: Scientific American. Published by Springer Nature (London, ENG, UK) on 2022 Apr 01. URL: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-father-of-modern-neuroscience-discovered-the-basic-unit-of-the-nervous-system/; DOI: 10.1038/scientificamerican0422-50.

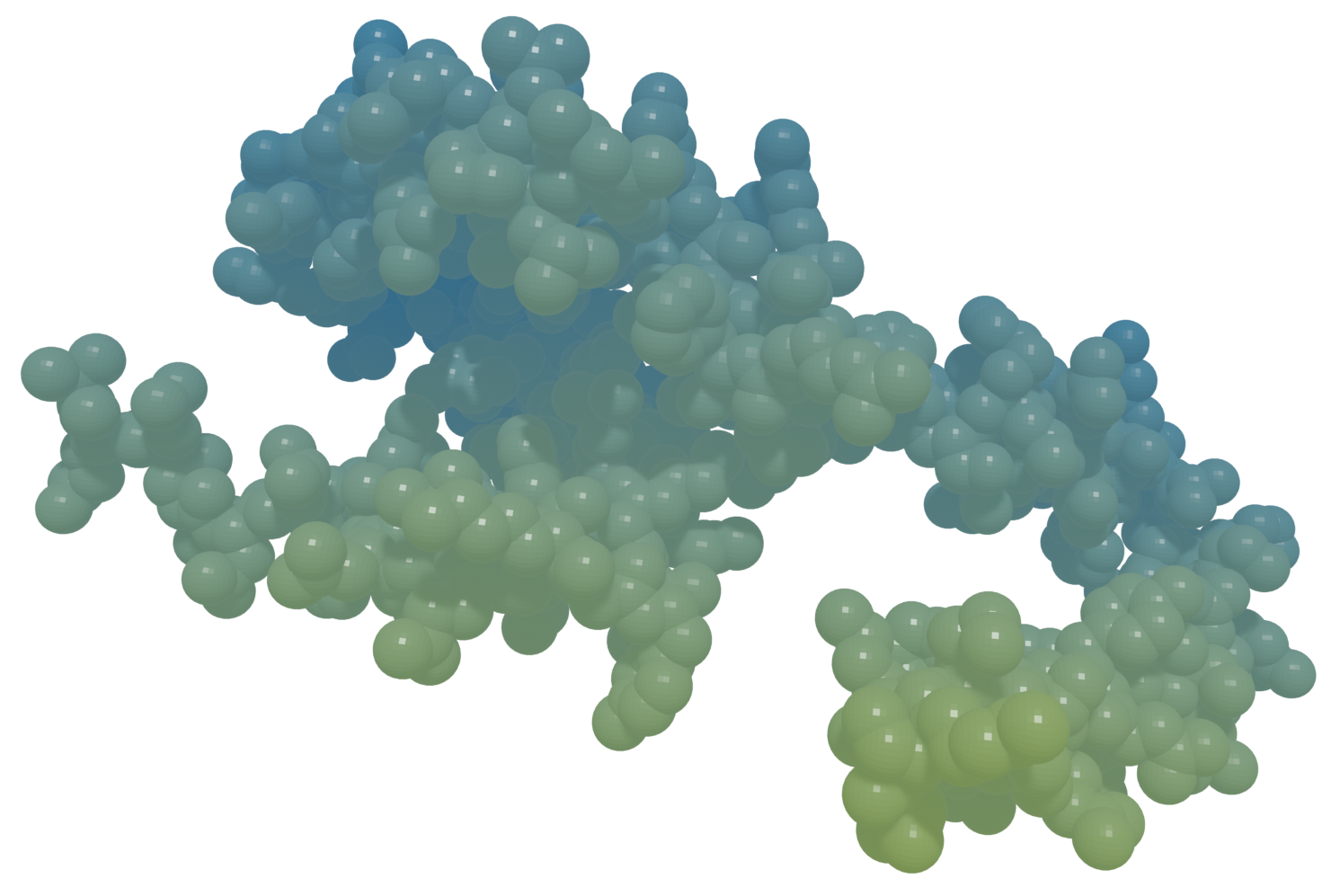

“Pío del Río Hortega and the Discovery of the Oligodendrocytes” by Fernando Pérez‐Cerdá, María Victoria Sánchez‐Gómez, Carlos Matute. Vol. 9, art. 92 from: Frontiers in Neuroanatomy. Published by Frontiers Media (Lausanne, VD, CH) on 2015 Jul 06. URL: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroanatomy/articles/10.3389/fnana.2015.00092/full; DOI: 10.3389/fnana.2015.00092; PMID: 26217196; PMCID: PMC4493393.